Recently we took another look at Lorimer Moseley’s and David Butler’s 2015 paper, Fifteen Years of Explaining Pain: The Past, Present and Future, with an emphasis on the misconceptions that have arisen around the notion of teaching people about their pain.

Different from previous educational approaches

With these misconceptions highlighting what Explain Pain is NOT, the paper also describes what Explain Pain IS, specifically:

EP refers to a range of educational interventions that aim to change someone’s understanding of what pain actually is, what function it serves, and what biological processes are thought to underpin it. It refers to both a theoretical framework from which to approach pain treatment and also the approach itself. EP is not a specific set of procedures or techniques. It takes its key tenets from educational psychology, in particular conceptual change strategies, health psychology, and pain-related neuroimmune sciences. The core objective of the EP approach to treatment is to shift one’s conceptualization of pain from that of a marker of tissue damage or disease to that of a marker of the perceived need to protect body tissue. This new conceptualization is a pragmatic application of the biopsychosocial model to pain itself rather than to pain-related disability per se.

An explicit grounding in conceptual change theory is one way in which EP is clearly differentiated from previous educational components of pain programs and CBTs [Cognitive Behavioural Therapies]. Conceptual change learning is specifically shaped around challenging existing knowledge and knowledge structures, rather than simply learning new information, and refining learning strategies that engage new and potentially challenging concepts.

Not easy

Conceptual Change, essentially, is learning in the presence of existing knowledge, and it isn’t easy – for the learner, or for the instructor. Learning involving conceptual change acknowledges that the learner already has pre-conceived notions about a particular topic (in this case pain), suggests that these conceptualisations are erroneous or inaccurate (for example, the idea that pain is an accurate marker of tissue damage), and describes both the process of changing these erroneous misconceptions and the outcome of taking on new, more accurate ideas. Pre-conceived ideas, especially those reinforced by societal and cultural beliefs can be deeply held and emotionally fraught with challenge. Consider again the widely held public belief that pain is a marker of tissue damage, and the skill and care that is required to challenge this belief in an individual with a 10 year history of low back who has been told that they have multi-level degenerative disc disease, should never bend, and has multiple other disc-conceived strictures placed upon them about how to move, live and (not) work.

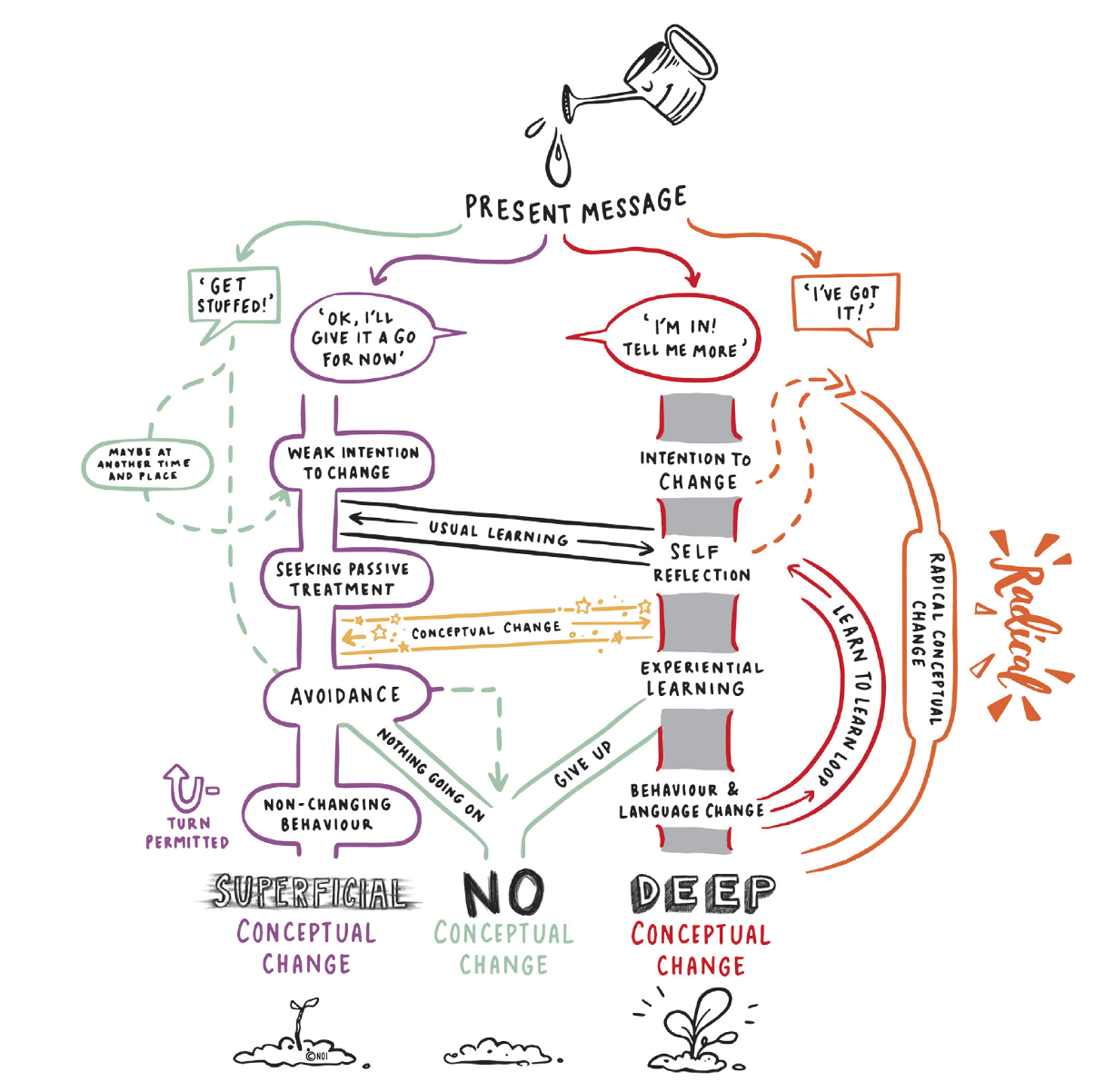

It should be of no surprise then, that attempts at conceptual change in relation to pain are not always successful, but rather can have sub-optimal outcomes. The image below captures the multiple potential outcomes of an attempt at conceptual change.

Note the three outcomes; superficial, no, and deep conceptual change, this last being our goal. Note the multiple pathways to each and the shifts between pathways that can take place. The possibility for radical reconceptualisation is there, as is the U-turn away from superficial conceptual change with the possibility of taking a different road. Reflect on the initial responses, everything from “Get Stuffed!” to “I’ve got it” – what’s the most common response in your clinical experience?

Some helpful pointers

A huge body of literature in the educational sciences supports the notion that conceptual change (in nearly any educational domain, including those much less personal than pain) is difficult, and there is no clear consensus on how to make it easier, or conceptual change educational interventions more effective. But there are some helpful pointers:

1. Education about education and learning can help. Very few health professionals have been taught anything about teaching others, yet ‘education’ is always suggested as a key factor in good treatment

2. Knowing the difference between learning in the absence, and in the presence, of pre-existing knowledge is of vital importance. The ‘education’ provided by health practitioners (see 1. above) often assumes the former and is frequently nothing more than a ‘knowledge show’ with the provision of facts, figures and information. People experiencing pain are experts in their own experience, often with deeply held, well-formed ideas about their pain – facts and figures and information (especially about anatomy and physiology) is not likely to change their conceptualisation, in fact it is possible that it will entrench it further.

3. Conceptual change requires some conflict – of ideas. The process of conceptual change involves the comparison of existing conceptualisations with new (hopefully more accurate but often less intuitive) conceptualisations, highlighting the differences and conflicts, and the facilitation of the accomodation of the new conceptualisation. This takes permission (very often a missed step), skill, deep knowledge and empathy on the part of the person facilitating change, and tremendous courage from the person taking on new conceptualisations

4. Resources are important. Pictures, props, stories, multimedia and metaphors are just some of the resources you need – before you embark on conceptual change.

5. Understanding the kind and level of misconception a person holds can help guide the development of a conceptual change strategy – some ideas to get you started on this here and here.

Tool up with knowledge, skills, clinical wit and wisdom

If Explain Pain is about conceptual change, the answer to the question as to whether to change or not is not a simple one. As a therapist it behoves you to tool up with knowledge, skills, and even a little bit of clinical wit and wisdom, in order to be able to facilitate this change effectively.

There’s a whole lot more on conceptual change in an Explain Pain course, and in Explain Pain Supercharged. EP has continued to grow over its 20 years and 2020 is the biggest and busiest year yet with EP courses around the globe.

-Noigroup

I first came across NOI through a physio very sympathetic to NOI in 2012 doing the left/right exercises. I soon gave up as It was very uncomfortable to sit at the computer.

Eight years later still on lyrica, Zoloft SR paracetamol, having done multiple sessions of targeted Pilates and over the past 12 months multiple SIJ blocks, and recently RFD on the SIJ, multiple RFD’s on the piriformis I find this article of interest and worth exploring.

I still use my 2012 physio as a knowledge base but use a physio closer to home for day to day physio.

I am sick of it and just want to get over it.

Mine started in 2007

So true, conceptual change from bits (grains) to full concepts (sandcastles) ask the expert patient, work with them, engagement is the key

Great model to understand how change is important in a behaviour setting or musculoskeletal pain situation. Thank you for sharing this.