I feel very fortunate to have been invited to attend the 2018 NOI EP3 course in Melbourne as a science correspondent. At EP3 it was clear that a contemporary understanding of pain and a biopsychosocial approach to help people living with persistent pain lies at the heart of the work of David Butler, Lorimer Moseley and Peter O’Sullivan. Over the course of the of three days, one thing that really stood out for me was how the emerging theory of Predictive Processing appeared to be a common theme across the science, educational teachings and clinical practice of these three leading experts – even if they didn’t realise it.

Predictive Processing Explained

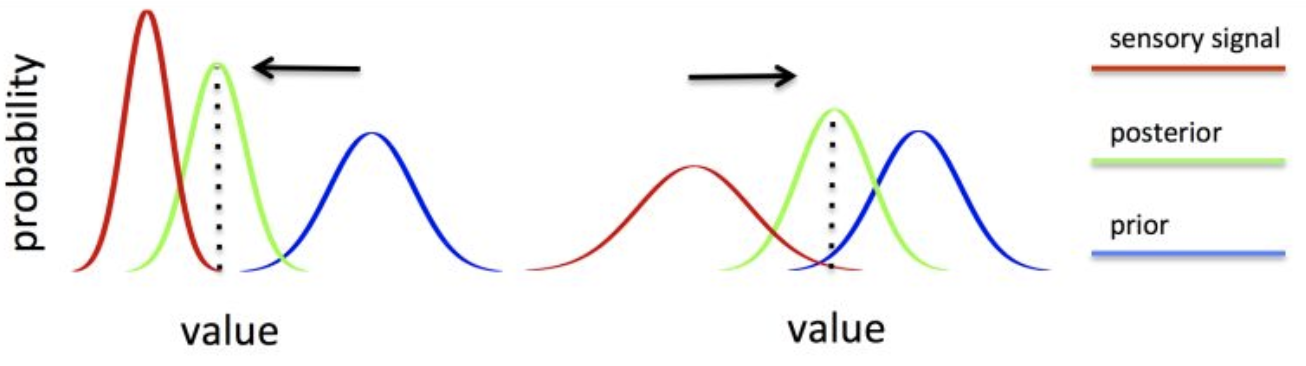

It has become widely acknowledged in the cognitive sciences that one of the key functions of the brain is prediction. Predictive Processing (PP) is one formulation of this idea that provides a unified framework for how the brain operates and processes copious streams of information. In this view, perception is a process of informed guesswork or inference (to a ‘posterior probability’), in which the brain interprets (mostly unconsciously) various sensory signals in accordance to one’s expectations or beliefs (known as priors in PP) via data-driven (bottom-up) and prediction-driven (top-down) connections.

According to this theory, the brain is continually testing the accuracy of an internal model (partly constituted by the very structure of the brain itself) by formulating predictions for the causes of the sensations it receives – the light on our retinas, sound waves in our ears, interoceptive signals from within the body and so on. These predictions are then compared, at multiple levels of a neuronal hierarchy, against the actual sensory input received. At each level of this hierarchy, higher-level top-down pathways carry predictions to lower levels whilst lower-level bottom-up pathways carry prediction error. In this manner, it is only the difference (prediction error) between what the brain expects (downward flowing predictions) and what it receives (incoming sensory data) that is passed up the neuronal hierarchy.

Discrepancies between predictions and sensory data are resolved at every level of the hierarchy through prediction error minimisation. Prediction errors can be minimised by higher levels of the hierarchy revising the internal model to produce predictions that better match the input. In the PP scheme, this leads to stable perception (posteriors) and a model that is able to produce more successful predictions in the future (i.e. learning). Prediction errors can also be minimised by holding the top-down predictions constant and changing the bottom-up input to match the model, such as by moving the eyes and head to alter sensory flow. In this way, action is introduced to the PP scheme, not as a separate function, but rather as part of a continually rolling perception-action cycle. This reciprocal exchange of neural signals between top-down (predictions) and bottom-up prediction error (sensory signals) at each level of a complex and dynamic neuronal hierarchy ultimately forms the organism’s optimal inference (guess) of the causes of such inputs, based on what it already knows about how the world is structured and functions.

Put simply, the brain is a “predictive machine” – we perceive the brain’s best guess of what’s out there in the surrounding world (the causes of sensory input) based on an optimally tuned balance of what we already ‘know’ and the data we receive from the outside world. Here’s an example of what I mean by this, what I if told you that you read this sentence wrong?

Read that last sentence again!

The process of change from a Predictive Processing framework in relation to persistent pain

On day two of the three-day event, Peter O’Sullivan demonstrated his Cognitive Functional Therapy (CFT) approach with an invited patient, Russell. Russell had experienced persistent low back pain for more than 30 years, had undergone multiple surgeries, and was convinced that he was only going to get significantly worse as he continued ageing. For me, the interaction between Peter and Russell was one of the biggest learning experiences of the event.

Here’s a look at the interaction through the lens of Predictive Processing:

Existing beliefs/priors – Peter took the time to actively listen to Russell’s story. In order to create a safe environment, build trust and develop a strong therapeutic alliance Peter gave Russell the opportunity to express his feelings about his back pain, discuss his priors (knowledge, beliefs, fears and expectations) and validate his experience whilst paying attention to his use of metaphoric language and safety behaviours (e.g. tensing, holding breath, guarding, avoiding load etc.). The interaction revealed that Russell was extremely fearful of moving and loading his back, particularly bending, twisting and lifting. Unfortunately, these priors were largely due to the harmful messages and non-evidenced based advice he had previously received from health care practitioners. Russell inaccurately believed that his back was damaged, fragile and untrustworthy – the perfect recipe for creating DIM (‘Danger In Me’) messages and one highly influential (i.e. large, efficient and imprecise) back pain neurotag. It was clear that over time, Russell had acquired strict ‘rules’ surrounding his back pain that had been reinforced by the conflicting messages he had received – “don’t bend, don’t twist and don’t lift, but still sit, walk and move”.

Peter summed it up very nicely when he said to Russell:

“It’s like someone’s saying drive your car but put your handbrake on at the same time.”

Prediction error – Peter challenged and disconfirmed Russell’s prior beliefs through experiential learning. He asked Russell to flex his back to pick something off the floor and he got Russell to do this repeatedly while making him aware of his guarding, breath holding and grimacing. He got Russell to continue bending and lifting (at times on one leg) while relaxing, breathing and smiling – even laughing at times.

Within the frame of PP, all of these new experiences would have led to significant prediction error as Russell began to violate his previous expectations and move in novel ways. This prediction error would likely have been occurring right through the neuronal hierarchy from high level more abstract ‘beliefs’ about spines being vulnerable and weak, down to the receptors and spinal cord where beliefs (not the conscious, cognitive kind) are couched perhaps in terms of predictions about expected proprioceptive and nociceptive input.

All of this prediction error clearly led to…

Internal model updating – within a very short period of time, Russell was moving differently and his internal model as it related to his back and back pain had fundamentally changed. Since his interaction with Peter, Russell has been engaging in his most beloved activities such as jogging, having a round of golf and playing with his grandchildren – all things he never saw himself doing again, until he attended EP3! Peter modelled confidence, validated his experience and gave Russell permission to move which allowed him to learn that his back was intact, strong and trustworthy – the perfect recipe for creating SIM (‘Safety In Me’) messages.

To paraphrase something that Lorimer said during the event:

“Bioplasticity got you into this mess, and bioplasticity can get you out again”.

Equally,

Predictive Processing got you into this mess, and Predictive Processing can get you out again!

There is a great deal more to be understood about Predictive Processing – especially how it might relate to pain, persistent pain, and recovery. But the promise of this approach as a unifying theory of how the brain works is in its potential to provide a rich and deep story for perception and experience – maybe even consciousness – and offer an explanation for how current successful treatment approaches may work, allowing refinement and improvement, while suggesting completely new and novel treatments that leverage prediction error and internal model updating.

I hope I have inspired you to read some more on Predictive Processing and how it can be used to understand pain. If so, there are some resources here, here and here.

In the words of Dr Seuss:

Today is your day! Your mountain is waiting. So… get on your way!

-Caitlin Howlett

* My Thanks to Tim Cocks for some helpful discussion and comments on earlier drafts of this post.

Caitlin is a PhD Candidate at the Body in Mind research group at the University of South Australia. Her PhD thesis is investigating the differences in cognitive and mental flexibility between those with and without persistent pain. She graduated from UniSA in 2018 with a Bachelor of Psychology (Honours). She is highly passionate about, and fascinated by, the complex nature of the human brain – particularly its malleability and the influence this can have in the development and recovery of persistent pain. You can follow her on twitter @CaitHowlett

Caitlin is a PhD Candidate at the Body in Mind research group at the University of South Australia. Her PhD thesis is investigating the differences in cognitive and mental flexibility between those with and without persistent pain. She graduated from UniSA in 2018 with a Bachelor of Psychology (Honours). She is highly passionate about, and fascinated by, the complex nature of the human brain – particularly its malleability and the influence this can have in the development and recovery of persistent pain. You can follow her on twitter @CaitHowlett

References:

Hohwy, J. (2013). The predictive mind. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Friston, K. J. (2010). The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138. doi: 10.1038/nrn2787

Wiech, K. (2016). Deconstructing the sensation of pain: The influence of cognitive processes on pain perception. Science, 354(6312), 584-587. doi: 1126/science.aaf8934

Tabor, A., Thacker, M.A., Moseley, G.L., & Kording, K.P. (2017). Pain: A statistical account. PLoS Computational Biology, 13(1), 1-13. doi: 10.1371/ journal.pcbi.1005142

Ongaro, G., & Kaptchuk, T.J. (2019). Symptom perception, placebo effects, and the Bayesian brain. Pain, 160(1), 1-4. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001367

2019 NOI Courses Australia and New Zealand

AUCKLAND | 15 – 17 MARCH 2019 | EP+GMI *FULL*

AUCKLAND | 23 – 24 MARCH 2019 | MONIS *FULL*

ADELAIDE | 6 – 7 APRIL 2019 | MONIS

HOBART | 3 – 5 MAY | EP+ GMI *Last seats remaining*

KINGSCLIFF | 14-16 JUNE | EP+GMI

MELBOURNE | 5-7 JULY | EP+GMI

NOOSA | 2-4 August | EP+GMI

SYDNEY | 23-25 August | EP+GMI *NEW LISTING*

ALBURY WODONGA | 18 – 20 OCTOBER | EP+ GMI

Beautifully written making sense of a complex subject 👍😘

To put it another way, Peter used exposure therapy to help habituate/extinguish a conditioned response. I wonder if there has been any research on how many relapse post CFT as is seen in the high levels in exposure in psychotherapy (3 in 5- Craske). Also does flooding beat graded exposure?. Has anyone tried using scapolamine or propanolol post CFT exposure to help alter hippocampal integration as seen in positive outcomes for reducing relapse in anxiety and phobia?.

I love reading the predictive coding and free energy principle literature, as difficult as it is, but I think easier exposure models, which are the meat of what we are working with, are easier to translate into our manual therapy practices.

Nick, I agree.

The way Peter established and maintained the relationship was admirable and illustrates the sort of interaction that should be the norm, and in itself would have a positive effect on the pain sufferer. In respect to the procedure, the question arises, “Is this not an example of operant conditioning of pain behaviour?”

There is certainly much interest in predictive processing as it might provide “a unifying theory of how the brain works”.

But I must express considerable doubt as to its potential to provide both “a rich and deep story for perception and experience” and “a theory for persistent pain”.

Been thinking about PP and pain for a number of years after reading Andy Clark’s excellent book Surfing Uncertainty. PP certainly adds weight to the science of pain medicine. Thanks for the piece.