Paul Bloom is a professor of Psychology at Yale University. He’s obviously not afraid of controversy as in his latest book he is Against Empathy. In his own words this is, to some, akin to

“being against kittens, a view so outlandish that it can’t be serious”

A recent review in The Guardian discusses the main themes of the book,

“Feeling your pain is all well and good but not necessarily the best trigger of an effective moral response. Indeed, he [Bloom] argues that an ability to intuit another’s feelings might well be an aid to some dubious moral behaviour. A low score on the empathy index is commonly believed to be a feature of psychopathy, but many psychopaths are supremely able to feel as others feel, which is why they make good torturers.

Bloom, it should be said, is not in favour of an indifferent heartlessness. Indeed, his trenchant stand against empathy is an attempt to encourage us to think more accurately and more effectively about our relationship to our moral terms. He pins his colours to the mast of rational compassion rather than empathy, and it is a central tenet of the book’s argument – I think a correct one – that there exists a confusion in people’s minds about the meaning of the two terms.”

But you can hear it from the horse’s mouth in an in-depth and wide ranging interview on Sam Harris’ podcast Waking Up – Abusing Dolores:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/297553335″ params=”color=ff5500″ width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

In the interview, Bloom discusses an experiment where soccer fans view scenes of others (apparently) receiving electric shocks. The neuroimaging data suggests that when the viewed person receiving shocks is a fellow supporter (dressed in team colours) the participant is empathetic and reacts almost as if they are receiving the shocks. But… when viewing a person receiving receiving shocks dressed in a rival’s team colours, empathy shuts down and there is more of a pleasure response.

“empathy is biased and narrow and parochial and I think leads us astray in a million ways… [but] compassion is a bit different, so my argument with what we should replace empathy with for decision making is cold blooded reasoning, where you judge costs and benefits… where you ask yourself what can I do to make the world a better place, what could I do to increase happiness, to reduce suffering…”

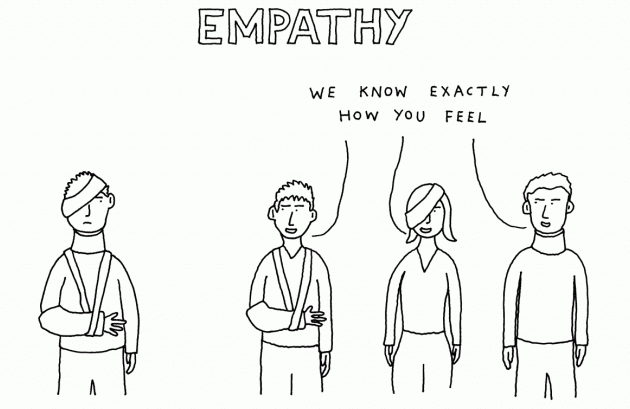

Bloom explains that you can see someone suffering and feel their pain – you can empathise with them, but you can also feel compassion which is different (in his terminology); compassion is feeling care for another human being, and a desire to help them and alleviate their suffering, to do something about it – it is more active.

The podcast’s eponymous Dolores, a character from the series Westworld who despite appearances is a highly sophisticated machine, is raised in a discussion of the additional moral challenges we will face as we hurtle towards a world containing high level Artificial Intelligence (AI). For example; how will we program driver-less cars to respond when faced with an impending accident – what if killing a pedestrian will save the life of the car’s occupants? And how will we treat AI agents, like Dolores who are ‘machines’ but look and act just like us?

It’s a long interview, but fascinating and worth listening to. Download it and listen to it on the bus, or as you drive your non-AI car.

But empathy is essential in the clinic…

Is it? This Aeon piece questions whether empathy is useful in doctor-patient relationships

Empathy is an overrated skill when dispensing medical care

We’ve long assumed that the empathising doctor is the better doctor, but both aspects of empathy – the cognitive and the emotional – can malfunction. From the cognitive end, our ability to walk in someone else’s shoes is biased and not-neutral; we walk easier in shoes that fit us. We are more inclined to feel empathy for attractive people and for those who look like us or share our ethnic or national background.

On top of all this, medical care is an active feat, while empathy, though motivating, does not in and of itself require action… We want our doctors to acknowledge our needs and act accordingly, yet we don’t actually need them to mirror our pain.

In fact, this final requirement is most closely related not to empathy but to compassion – defined among emotion researchers as the feeling that arises when you are confronted with another’s suffering, including the desire to help. This non-empathetic compassion – a more distanced love and kindness and concern for others – might act as a bridge between recognising the other’s feelings and providing care without the detriments of empathy. Since compassion does not require identification with the patient, it can help in performing good care as a professional duty, building trust, and treating someone according to his or her needs, while avoiding cognitive biases and empathetic distress. (emphasis added)

Against empathy, for compassion

Perhaps it’s all just word games, what one person means by empathy is encapsulated by what another means by compassion? But the distinction that Paul Bloom makes between empathy being passive – feeling another’s suffering, and compassion being active – wanting to do something about another’s suffering, seems worth thinking about. And while Bloom is, by his own admission, against empathy, he is very much for compassion.

Back to Dolores

Finally, back to Dolores – if Bloom is correct in his distinction between empathy and compassion, in the not too distant future when we welcome humanoid agents, well beyond the uncanny valley and with strong AI, how will we be empathetic towards a being that has no feelings? And despite their apparent lack of consciousness, would a truly intelligent ‘machine’ that looks like us, talks like us, and appears to suffer like us be deserving of our compassion?

Trivial? Maybe. But consider this; we’re still struggling with what to do about the possibility of fish pain – perhaps it’s because we can’t empathise with a fish and we rely on empathy too much? And what are the consequences for people with whom we can’t empathise – end of life decision making for the locked-in patient, or pain management for a Parkinsonian patient whose face is a mask (the under-treatment of pain in Parkinson’s patient is a significant problem)

Perhaps these are thoughts and conversations worth having.

-Tim Cocks

Melbourne SOLD OUT

Adelaide, 26-28 May EP + GMI

Wollongong, 14-16 July EP + GMI

Darwin, 4-6 August EP + GMI

Brisbane, 25-27 August EP + GMI

Newcastle, 8-10 September EP + GMI

Empathy and “pain”

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/01/150115122005.htm

“The secret of empathy: Stress from the presence of strangers prevents empathy, in both mice and humans”

2015

“In the new study, Mogil and his team compared the reactions of undergraduate students to painful stimuli in various scenarios: alone; with a friend; with a stranger; between two strangers given a stress-blocking drug; and between two strangers who had spent 15 minutes playing the video game Rock Band® prior to testing.

The student participants were asked to submerge their arm in ice-cold water and rate their pain. These pain scores remained the same whether they experienced the pain alone or sitting across from a stranger. However, the pain actually increased when these students put their arms in ice water across from a friend.

“It would seem like more pain in the presence of a friend would be bad news, but it’s in fact a sign that there is strong empathy between individuals — they are indeed feeling each other’s pain,” said Mogil.”