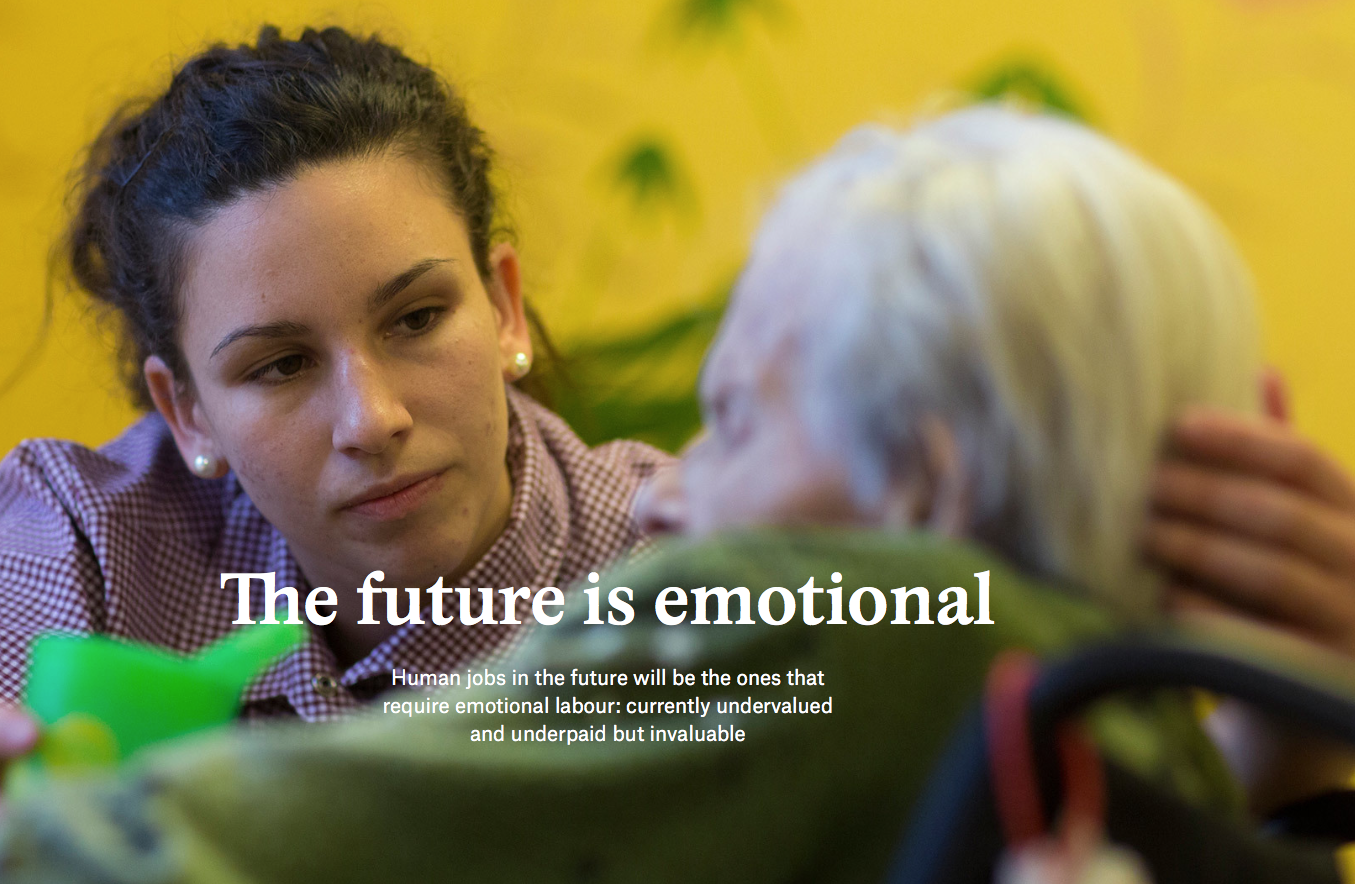

Thought provoking and highly relevant read for anyone involved in caring for others

…one of the toughest moments of a physician’s job is sitting with a patient, surveying how a diagnosis will alter the landscape of that patient’s life. That is work no technology can match – unlike surgery, where autonomous robots are learning to perform with superhuman precision. With AI now being developed as a diagnostic tool, doctors have begun thinking about how to complement these automated skills. As a strategic report for Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) put it in 2013: ‘The NHS could employ hundreds of thousands of staff with the right technological skills, but without the compassion to care, then we will have failed to meet the needs of patients.’

Some other key ideas worth thinking about:

– While the advance of technology will continue, very few people will actually work in highly specialised, sophisticated technological jobs – rather the information revolution will free us (and perhaps force us) into more emotionally intensive jobs requiring ‘soft skills’

– The central role of emotional labour has long been ignored – police spend 80% of their time in service work (including mediating disputes and responding to mental health crises) yet training almost exclusively focuses on weapons use, defence tactics and criminal law

“Predictably, there are regular reports of people calling the police for help with a confused family member who’s wandering in traffic, only to see their loved one shot down in front of them.”

– Jobs for doctors and surgeons are predicted to rise by 14% in the US between 2014 and 2024 while the top three direct-care jobs – personal care aide, home health aide and nursing assistant – are expected to grow by 26%

– The most significant skills required of direct-care trainees are coping with filth, violence and death.

– People from “working-class” backgrounds tend to have sharper emotional skills than wealthier, more educated people.

“Those who succeeded possessed skills they’d acquired growing up in working-class families, where as girls they took part in housework, caring for children and elderly relatives, and learned to be stoic in the face of heavy demands. ‘Clearly the experience of domestic work, serving others, denying their own needs (eg for regular sleep at night, for time off on Sunday) were demands to which these working-class girls were well-accustomed by the age of 16,’ Bates wrote.”

– ‘A better education’ might not be the best way to improve the situation of low paid care workers

“…assuming that more time in the classroom is key to making ‘better’ workers fundamentally disrespects the profound, completely non-academic skills needed to calm a terrified child or maintain composure around a woman playing with her own faeces.”

– Formal training in how to ‘act’ more empathetically may not be the answer

“As valuable as formal training in emotional skills might be, it’s not at the heart of what makes people successful in emotional labour. Hochschild noted that ‘surface acting’ – creating the appearance of an appropriate emotion – is harder on workers and less effective than ‘deep acting’ – really summoning up those feelings.”

– And a warning about the ever present drive for more ‘efficiency’ from emotional workers

But applying the metric of efficiency to the expanding field of emotional labour misses a key promise offered by technological progress – that, with routine physical and cognitive work out of the way, the jobs of the future could be opportunities for people to genuinely care for each other.

-Tim Cocks

WOLLONGONG 14-16 JULY EP+GMI

SYDNEY 29-30 JULY MONIS (SOLD OUT)

DARWIN 4-6 AUGUST EP+GMI

BRISBANE 25-27 AUGUST EP+GMI (GMI SOLD OUT)

NEWCASTLE 8-10 SEPTEMBER EP+GMI

SYDNEY 3-5 NOVEMBER EP+GMI

Very profound Tim 👏 And very true 👍

Thank you for this. Thank you for NOI that you have a place to share this with our profession.

Thanks Tim – a great piece.

“the jobs of the future could be opportunities for people to genuinely care for each other”.

This could start right now!

David