Philosopher Sandy Grant in Aeon on Wittgenstein and his language-games:

How playing Wittgensteinian language-games can set us free

We live out our lives amid a world of language, in which we use words to do things. Ordinarily we don’t notice this; we just get on with it. But the way we use language affects how we live and who we can be. We are as if bewitched by the practices of saying that constitute our ways of going on in the world. If we want to change how things are, then we need to change the way we use words. But can language-games set us free?

It was the maverick philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein who coined the term ‘language-game’. He contended that words acquire meaning by their use, and wanted to see how their use was tied up with the social practices of which they are a part. So he used ‘language-game’ to draw attention not only to language itself, but to the actions into which it is woven. Consider the exclamations ‘Help!’ ‘Fire!’ ‘No!’ These do something with words: soliciting, warning, forbidding. But Wittgenstein wanted to expose how ‘words are deeds’, that we do something every time we use a word.

…We are humans, the ones who live together in language in the particular way that we do, a way that involves distinctive social practices.

The remainder of Grant’s piece gets a bit technical, you can read it if you like, but these first few paragraphs do all the work that we need here; the idea that language is an extension of our actions and behaviour. Moreover, that language is not simply words, but a shared practice that we exist within, where the meaning of words is determined by agreed upon rules for their use, rather than any objective truth.

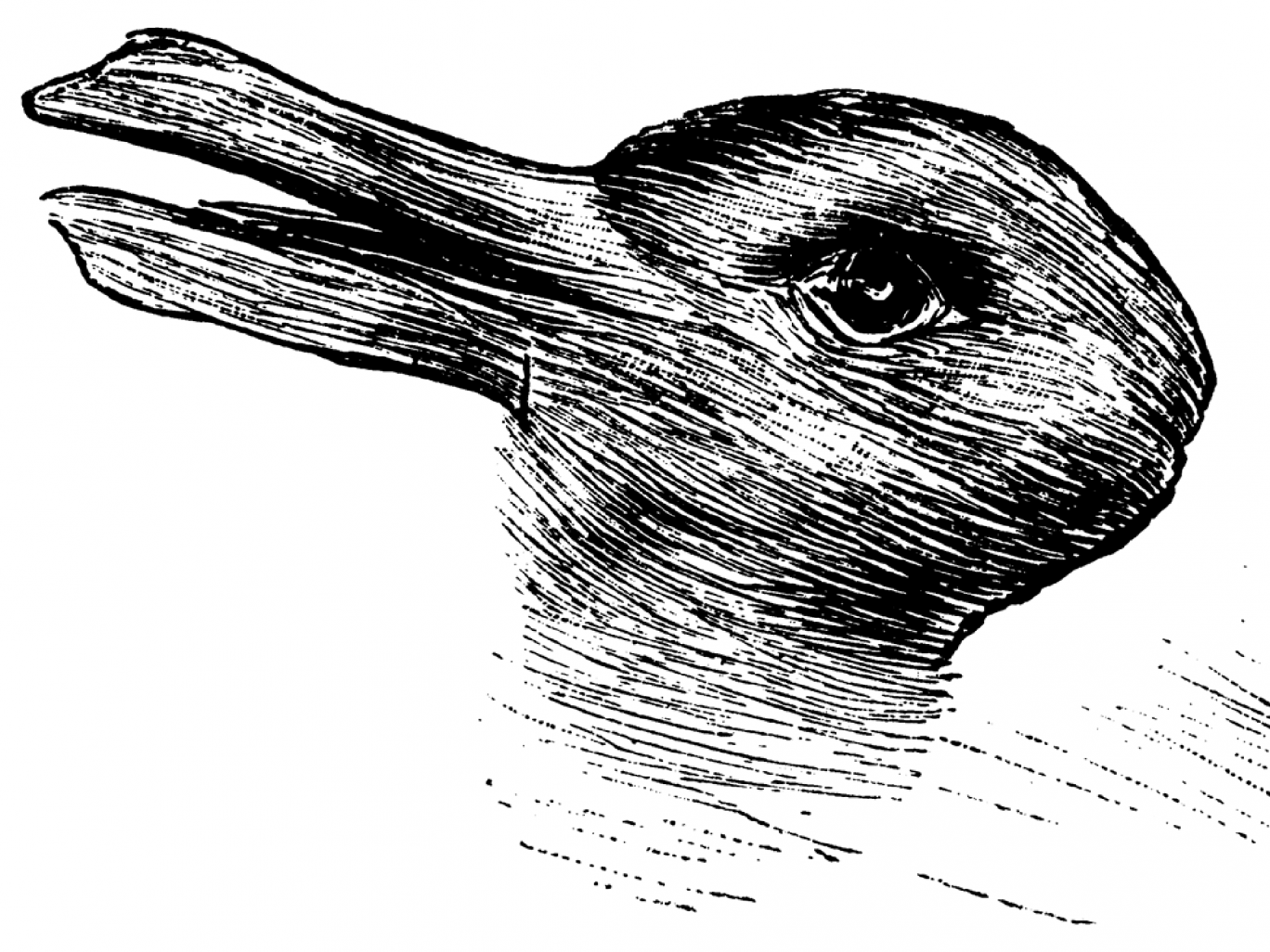

Look at this duck

Wittgenstein was also interested in how language can influence how we see – how we experience the world and how we share this with others. Take for instance, the following image of a duck, made famous by Wittgenstein in his Philosophical Investigations –

Of course, I’m aware that I didn’t fool anyone – you immediately recognised the image as the post’s eponymous Duckrabbit – an ambiguous figure that can be seen as either (but not as both at the same time) despite the image itself never changing. But undoubtably, my use of the word duck did something to you and influenced your initial perception of the figure.

From the moment they walk in the door

I have a small picture of a duckrabbit on the wall in the clinic here at NOI – its reminds me that from the moment a patient walks in the door, the words I use are doing something to the other person as we share an interaction. Additionally, the ambiguity reminds me to tread carefully as we engage in a language-game and attempt to learn the nuances of its rules – as they explain their experience, who am I to tell them whether it is a duck or a rabbit.

-Tim Cocks

Tim, here is another of Wittgenstein’s pointed aphorisms that applies to all who think that they are explaining pain to another person:

(Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 4.5): “The general form of propositions is: This is how things are.” That is the kind of proposition that one repeats to oneself countless times. One thinks that one is tracing the outline of the thing’s nature over and over again, and one is merely tracing round the frame through which we look at it.

A pointed challenge indeed, one which perhaps begs the question as to whether one can ever do any more than ‘trace round the frame we look through’ when it comes to our pain, let along another’s?

I read this from Spain as I am grappling to understand and make myself understood in Spanish, an unusual experience for an Aussie, and always a very humbling one. One of the challenges that I face each time I open my mouth is not just remembering the vocab to construct the basic sentence so it will mean something, but also constantly understanding and creating new or different but correct ways of saying the same thing- Incorporating nuances into the way I both speak and listen to conversations. It reminds me of the enormity of language, how true it is that we will never stop learning even our own language and finding new ways of saying and listening to things until we breathe our last breath. It seems that the Explain Pain journey is not unlike learning a new language- there are endless possibilities and we need to keep our eyes open and our ears to the ground!