This post originally appeared as an invited chapter commentary on the Body in Mind website.

I was delighted to be asked to present a chapter from the recent collection Meanings of Pain. Dr Smadar Bustan’s contribution- A Scientific and Philosophical Analysis of Meanings of Pain in Studies of Pain and Suffering, is a complex chapter with ideas deriving from a long philosophical tradition. The challenge for me was to do the chapter justice while offering readers of an easily graspable summary of the work.

Starting at the beginning

The chapter commences with a reflection on the experience of sitting across from chronic pain sufferers reporting unrelenting pain at the “highest pain imaginable” level, while observing “no tangible, apparent, physical expression to match the elevated scores and the descriptions of a torturous internal state”. This seeming paradox highlights the great challenge that pain, especially chronic pain, presents both the clinician and the researcher, and defies the notion that objectivity in medical judgements must be based on empirical facts. Notably, the establishment of the reliability of objective, third person behavioural approaches to assessing pain has ultimately relied on correlation with subjective, first person pain report. This presents an unavoidable circularity that illustrates the futility of trying to develop purely objective measures for pain.

Models of pain and the meaning suffering

To the traditional model of pain, with its sensory-discriminative (intensity) and affective-motivational (unpleasantness) dimensions, a third dimension is suggested – “pain-related suffering”. Exploration of the meaning of this suffering has led to distinctions between suffering experienced as a “feeling that will come to an end” and suffering that is experienced as a “prolonged condition… a situation of endless affliction such as the loss of a child or a chronic pain condition… making one’s torment the basis of everlasting reality”. This latter kind of suffering – “existential suffering” is posited as a fourth and final dimension of pain. However, understanding the meaning of pain and suffering is not trivial, and each individual will experience a unique process of acquiring meaning for his or her own pain that can evolve across time and experience.

The evolving meanings of pain

“The perception of pain evolves depending on its application within a context in a given time frame… the meaning of pain is therefore never fixed. This is particularly relevant to conditions becoming chronic because in these circumstances, pain is often first thought of as a burden requiring strength and adaptable coping strategies on the way to recovery, before turning into a permanent condition representing a forever lasting, defeating threat.”

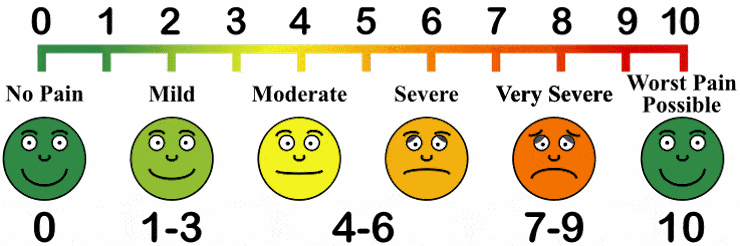

A slippery beast indeed. The utterance pain may ‘point to’ a vast array of experiences for any one individual from “excruciating [to] pleasurable, following its form of occurrence (sexuality, torture/illness)” demonstrating the potential chasm in understanding created by the possible uses of the one word. Immediately, the use of a 0 – 10 score for pain, either in the lab or in the clinic, seems hopelessly inadequate.

Deciphering pain and suffering

Two types of meanings in the expression of pain and related-suffering can be further unfolded. A more objective type of meaning evoking the qualities, the feel, of pain symptoms – as expressed in a quote from a patient “suffering is to feel hurt, it hurts you, incapacitates your body and keeps you from living normally.” And an implied meaning that “reflects the internal value a person ascribes to his lived pain (annihilating, threatening, diminishing) and suffering.” From the same patient; “I suffer because of my health problems. This is not a mental suffering, rather physical suffering because it prevents me from carrying out my plans” (emphasis added).

This is a nuanced distinction, but expanding the examination of pain and suffering beyond their more objective qualities allows a deeper understanding of what really bothers the patient. This is underlined by another patient example, that of a 50 year old woman with persistent neuropathic pain in her hands and feet, who reported her loss of femininity, “I lost my femininity because I cannot put [on] high heels. Even with earrings, I drop them every time” and existential suffering, “I feel like I am in a fog and I feel that everything is wrong, I’m not here…” as the greater determinants of her overall suffering.

A key aspect to the more nuanced implied meaning is the set of values held by an individual, challenging clinicians to “look attentively enough and acknowledge that there is something more than the scientific list of signs to account for” and to “go beyond the set of nociceptive and affective features coming together in a specific but quite mechanistic configuration” when trying to understand another’s pain.

Towards a tool for elucidating pain and suffering

Ultimately, the project is to develop a practical tool for deciphering pain and related-suffering meanings. The many considerations involved in the development and deployment of such a tool serves to summarise the key ideas in the chapter and conclude this post:

- Patients often find it hard to relate to current attempts to capture the experience and impact of pain via visual analogue scales or various questionnaires that do not “convey the patient’s full emotional state, especially the suffering resulting from the turmoil the person is undergoing”.

- Pain and suffering are often confounded, with the subtle nuances of the meanings of both lost. The resulting conflation of pain and suffering may manifest in the reporting of pain as 8 or 9 out of 10 for many months, with the numerical rating an attempt to express the true impact of a persistent pain state in the absence of satisfactory suffering-related understanding and language.

- The necessity of the merging of philosophy with science and medicine to “highlight suffering and pain as a lived event including their multiple facets” including situation, emotional state and cognition.

- The consideration that meanings for pain and suffering, and the utterances used to express these, are not just a list of properties implying what the words refer to, but reflect different aspects of the experience based on very distinct sets of values.

Far from being an attempt to have the final word on the topic, Dr Bustan’s thought provoking and challenging chapter is a two fold invitation to the reader. Firstly, to delve deeper into their own understanding of pain and suffering. And secondly, when in clinical or research settings, to sit with patients and share an introspective journey to fully elicit and express the complete lived experience of pain, thereby profoundly validating and giving voice to that individual’s pain and related-suffering.

-Tim Cocks

Australian courses 2018

We ran 15 courses across Australia in 2017 – 13 sold out! We’re feverishly working on dates and venues for our 2018 calendar – we’ll be heading to Canberra and Warrnambool in April, Bendigo in May, Noosa in June, Cairns and Mildura in August, Perth in September, Hobart in October and putting on something special in Melbourne in November! We’ll be posting details very soon – keep an eye out her on NOIjam as well as our Courses Page

References

Bustan S (2016) A Scientific and Philosophical Analysis of Meanings. In: van Rysewyk S (2016) Meanings of Pain. Springer International Publishing, 2016. pp. 108-127.

Life is good but it could be so much better if only I wasn’t in constant pain. Then again maybe not as I don’t know what it feels like to be without pain. Maybe I would feel worse as if a part of me, a vital emotion were missing……..

I am currently reading The Knowledge Illusion which states that knowledge is a culturally shared experience ie I keep my knowledge of cars in my mechanics head.

Perhaps people with persistent pain would benefit from a team of professionals with differing skill sets- the physio, doctor, psychologist etc who meet together and working from a compassionate stance come together for the good of the patient. To not work with a “diagnosis” but rather to find ways of helping with the patterns of daily suffering that the patient encounters.This tallies with evolutionary biologist Nicholas Humprey’s theory that healing in ancient societies was a collective effort led by a Shaman for the good of the individual (The evolutionary basis of placebo).

As a solo practitioner I tell my patients that are expressing high degrees of suffering that “for the next 45 minutes we are two working as one solely for your good.That we both have expertise and if we combine our knowledge we may find new ways of moving forward”.

The greatest in roads I made into my own daily suffering was through a combination of pain knowledge, psychotherapy, physiotherapy and, most importantly true unconditional love from my wife……..I feel we have to pay attention, in varying degrees, depending on the person to both the “issues in the tissues” and the “thought viruses”. No one person can cover all those aspects…..