In 2017, Professor Michel Coppieters is running Mobilisation of the Neuroimmune System in Sydney, 29 – 30 July. Here’s David Butler’s NOInote explaining what this course is all about

Mobilisation of the Nervous System to Mobilisation of the Neuroimmune System

I wrote Mobilisation of the Nervous System about a quarter of a century ago while working in a hospital in Dartford, Kent – I remember thinking that only my family would buy it. I still find it very humbling, but many people did buy it, and 25 years later, tens of thousands of participants have taken the MOTNS course. Although the course has been refreshed many times, it’s time for a major refresh – not just the name, but also the core underlying thinking and paradigms.

What’s new?

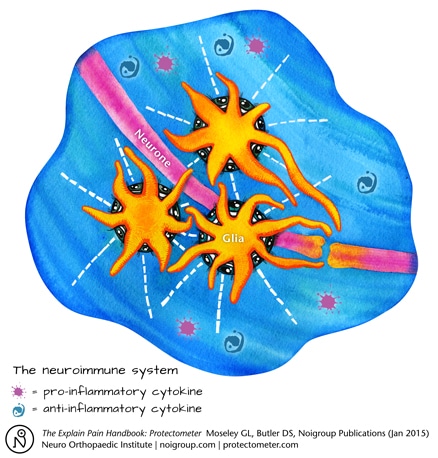

The major refresh is to acknowledge and incorporate the immune system. In retrospect we should never have missed it. Of the trillion or so cells in the nervous system only about half are neurones, the other half are mostly glia; historically dismissed as literally ‘glue’ – as packing and support for the neurones. But most of this “other brain”, such as microglia, astrocytes and Schwann cells, have immune functions and an intimate reciprocal relationship with neurones – the brain hasn’t changed, it’s always been a neuroimmune organ – it’s our thinking that needed catching up. The neuroimmune system is a critical player in learning, memory, movement and sensitivity, and neuroimmune thinking demands a far wider view of neurodynamics.

Another aspect of the refresh is one that is ongoing – taking on and incorporating the somewhat quieter but continuing, research into neurodynamics. Recent papers include Nee et al’s (2012) work, which demonstrates that neural mobilisation can be effective and safe for nerve-related neck and arm pain, or some emerging work which might question the notion of ‘musculoskeletal’ conditions such as ‘patellofemoral pain syndrome’ (Huang et al 2015).

But we mustn’t forget the quality of the old. For me, the two most comprehensive books on peripheral nerve problems are still Sunderland (1978) and Mumenthaler & Schliack (1991). They both reek of quality of clinical examination linked to research. Much of Sunderland’s work was carried out on soldiers post WWII. Sunderland helped me construct a science base for neurodynamics and I recall him saying that there was ‘no profession out there looking after the minor but often very painful peripheral nerve injuries’. Michel Coppieters work carries on this tradition and we look forward to featuring this in coming weeks on noijam.com.

Can you really move Schwann cells, microglia, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes?

You can – especially in peripheral nerves, cord and probably hindbrain. With my clinical science hat firmly on, I think it would be reasonable and sensible to suggest that associated connective tissues, the cells and the milieu probably enjoy a good wriggle, tease, and flush as part of their normal movement, especially when there is a bit of inflammatory soup around or fibroblasts needing a bit of polarisation (see Gilbert et al 2014 for some basic science support of this idea).

But embracing the immune system is much more than just the movement…

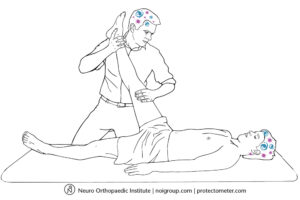

A Straight Leg Raise is antigenic

The term antigenic usually refers to a substance (pathogen) initiating an immune response. But movement (along with learning and thinking) can also initiate immune activity and thus can be called antigenic. A Straight Leg Raise (SLR) is a test of many things ranging from physical abilities of tissues in the leg, whether the owner of the leg likes the person lifting the leg, to how they perceive the quality of the elastic in their underwear. It is also a test of the precision and sensitivity of the neuroimmune architecture representing the movement and the meaning of the movement at that particular time. For example microglia and astrocytes in the brain and cord in their surveillance role repeatedly check for danger. If the SLR is deemed dangerous by the leg owner then the microglia and astrocytes may well contribute to modifying the brain representation of the SLR – including when the brain ‘decides’ it is safe to stop the movement.

The sensitivity of the movement will also likely be altered. At our recent Explain Pain 3 day course in Melbourne, Prof Bob Coghill spoke about ‘top down tuning’ of the peripheral nervous system and he provided a beautiful summary: ‘cognitive factors can powerfully shape the processing of afferent information, potentially through dynamic, task dependent tuning of afferent processing mechanisms’ – this really got us excited. To us, this suggests that not only can the meaning of a movement, in this case a SLR, have a neuroimmune effect on the brain, but the brain can then ‘tune’ the processing of incoming information in the periphery – thereby altering the messages the brain receives, which will then potentially influence cognition, which may have a further tuning effect and so on! Think of this next time you lift someone’s leg in the air! A ‘simple’ SLR doesn’t seem so simple anymore!

Whew!

We clearly have to be smarter at doing our active and passive neural mobilisations and adopt a much broader neuroimmune paradigm in our clinical reasoning. So much of this relates to the idea of context and meaning, and drawing the immune system in adds the notion of ‘self’ and neuroimmune responses to perceived danger to this ‘self’ – can you see how this might influence the range, quality and experience of a SLR depending on whether it is ‘self or ‘other’ doing the moving? Our assessment, intervention and education skills related to any sensitivity and stickiness exhibited when we move the nervous system can be refined and sharpened by this overdue integration of the immune system.

A final juicy morsel

The word ‘mobilise’ is often thought of as just meaning ‘move’. But mobilise has a broader meaning too – ‘to make ready for movement’, ‘to assemble or prepare something in response to need’ and to ‘liberate or excite quiescent material to physiologic activity’. These rich ideas are all incorporated into mobilising the neuroimmune system.

-David Butler

Useful Links

Bodily Relearning, Boyd BS

Neurodynamic techniques Handbook & Videos, Butler DS

The Sensitive Nervous System, Butler DS

References

Gilbert KK et al. (2014). Effects of simulated neural mobilization of fluid movement in cadaveric peripheral nerve sections: implications for the treatment of neuropathic pain and dysfunction. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy. DOI: 10.1179/2042618614Y.0000000094.

Huang B-Y et al (2015). Predictors for identifying patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome responding to femoral nerve mobilization. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2015.01.001.

Mumenthaler, M. and H. Schliack (1991). Peripheral Nerve Lesions. New York, Thieme.

Nee RJ et al. (2012). Neural tissue management provides immediate clinically relevant benefits without harmful effects for patients with nerve-related neck and arm pain: a randomised trial. Journal of Physiotherapy 58(1) pp 23-31.

Sunderland S. (1978) Nerves and nerve injuries. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

I love that statement from Prof Coghill!

The term “antigen” is in my opinion confusing and inappropriate when used in this context. I suggest “perturbation” might be preferable, as it better conveys the intent of the author.