Saurab Sharma is a physiotherapist who works in a clinical setting at Dhulikhel Hospital, Kathmandu University Hospital, and lectures at Kathmandu University School of Medical Sciences. I had the pleasure of meeting Saurab when he attended EP3, and PainAdelaide earlier this year and we’ve kept in touch. I asked Saurab if he might be interested in doing a bit of a Q&A for the ‘jam and he was happy to oblige.

Q: Saurab, tell me a little bit about where you work and the people you work with

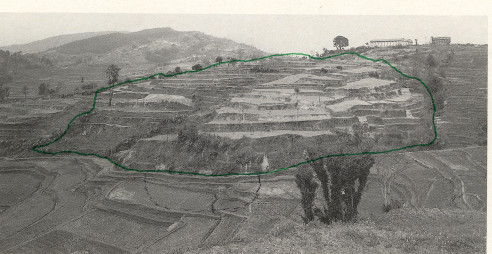

A: Dhulikhel Hospital is located 30 kilometers east of Kathmandu. Although the distance appears to be short, we receive patients from very remote areas and the characteristics of these patients is very different. Most of these patients are from low socioeconomic status, have not been to school, and most of them would have visited traditional healers and tried all other ways of management before visiting the hospital. Most of them get themselves examined only if the problem is chronic, and very severe which does not resolve by any other methods of treatment.

Q: What are your interests as a physiotherapist?

A: My interests include management of musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain conditions. However, in the process of using evidence based management approaches to various painful conditions, I realized that the direct translation of evidence to practice in Nepalese population is extremely challenging.

Q: What are some of the challenges you face as a physiotherapist?

A: Some of the challenges include very low socioeconomic status, poor educational background (most of these patients are uneducated), traditional beliefs about the cause of pain, chronicity of pain, severity of the problems, including onset of deformities, and unavailability of pain related outcome measures in Nepali language. The difficult geography of the country and low socioeconomic status restrict the patients from coming back to the physiotherapists for the follow up despite of very low treatment cost (less than one dollar). Thus, planning the treatment of these patients is extremely difficult because of these factors. As the most frequent treatment approaches a physiotherapist uses are exercises, pain education and assurance, graded motor imagery etc all require a systematic approach to management and require multiple visits.

Imagine a patient coming to you with complex regional pain syndrome three months following open reduction and internal fixation for distal radius fracture and all you have is “half hour” to treat him. Physiotherapist should be a magician to treat the patient in single setting. Thus, the treatment of the patient is quite challenging.

Q: Have you noticed any unique aspects in regards to the experience and understanding of pain in Nepal?

A: While treating patients with painful conditions in Nepal for over seven years, I identified various trends in the pain behaviours among patients in Nepal. I noticed that some group of patients have less threshold for pain and better pain tolerance than other groups. I also noticed that some of these have very high catastrophizing and fear avoidance behavior than others. These variations seemed to be specific to ethnic groups, geographical location, and religion. This could be true for patients in other countries as well, however, I found this humongous variation in a small country such as Nepal quite unbelievable. Because of these variations, clinicians require completely different management strategies for these sub groups; while one group require more attention, assurance and analgesics and thus they take longer time to recover. I also suspects that these are the subgroups that are more prone for having persistent pain or chronic pain.

Q: How did you get interested in research?

A: After noticing these variations in pain, my interest grew in investigating this using rigorous research design. I am currently in the process of developing a pain quality tool based on different words patients in Nepal use to describe their painful states. Further, I am in process of translating various pain related outcome measures to Nepali language including measures for pain catastrophizing, pain intensity, pain interference, pain tolerance and pain behavior etc.

Q: What aspects of pain research are you interested in?

A: I am interested in looking at psychological factors that can contribute to ongoing pain such as sleep disturbances, depression, optimism, resilience, behavioral activation and inhibition system. I am also interested in comparing these psychosocial aspects of pain among patients in Nepal with those living in the developed nations. By developing a sound understanding of pain science and with a keen interest in developing pain knowledge and management for developing country such as Nepal, I collaborated with Dr Mark P Jensen, Professor of Psychology in University of Washington, Seattle. This collaborative research protocol earned an International Association for Study of Pain Collaborative Research Grant for 2015.

Q: You’re also involved in promoting and developing physiotherapy in Nepal, can you tell me a bit about this.

A: I am a member of the physiotherapy subject committee member at Nepal Health Professional Council and an advisor to Nepal Physiotherapy Association. My goal is to help improve the standards of physiotherapy practice in the country with my colleagues by revising the code of ethics and introducing a license examination for physiotherapists in the country. Through the association, I am also actively involved in the ongoing professional development programs for physiotherapists in Nepal by organizing courses, workshops and conference. As the organizing secretariat for Nepal Physiotherapy Conference last year (NEPTACON-2014) which was a grand success, my colleagues and I brought together 14 experts in the field of physiotherapy from eight different countries, and had more than 300 participants from all over the world. The conference also included five pre and post conference workshops from these experts.

My thanks again to Saurab for taking the time to share his experiences.

You can find Saurab on Twitter as @link_physio and he has a blog at linkphysio.com – a “novel initiative to improve evidence based practice, share recent knowledge with physiotherapists, physiotherapy students in Nepal, and other developing countries.”

-Tim Cocks

I have heard and learned some amazing things about it, Thumbs up!

Thanks a lot Sudan. I will require support in my journey to fight pain in Nepal. I am sure you will be there.

Regards,

Saurab

Reblogged this on konviktion and commented:

sorry for all these painful posts but as we all know if we share the grief it will be lesser thanks for all of your patience and forbearance……………

Thanks your comments and for reblogging.

Regards,

Saurab

welcome 🙂

Reblogged this on saurabsharma's Blog and commented:

These are what I shared with NeuroOrthopedic Institute, Australia, when they asked me about my experience of treating patients with various painful conditions in Nepal, and how I happened to be involved in pain research that earned me and Prof. Jensen the International Association for Study of Pain (IASP) research grant.

Hi Saurab,

Many thanks for this.

I have always been intrigued ( and a little embarrassed) when I was teaching the pain section on a university manual therapy course in Australia with perhaps half or more of the students from Asia or India and reflecting that the prevalence of chronic pain in these students’ counties was half of what it was in mine. Admittedly such statistics are fraught with error but consistently show that the developed nations have more chronic pain than the so called less developed nations.

Maybe we should be learning more from you?

David

Thanks for the write up Saurab.

@David, I had no idea about the prevalence of chronic pain in 1st versus 2nd/3rd world countries. Interesting.

I think the prevalence of chronic pain here in the West is partly due to a mass, cultural belief phenomenon. We only need to look at the rise and fall of ‘RSI’ in the 80’s or ‘osteitis pubis’ amongst footballers in the early 2000’s, or childhood food allergies in current times. These mass fears come and go.

Of course our compensible bodies (WC and TAC) do their best to scare the hell out of people with their advertisements of people wrenching and crushing and ripping their bodies apart! This fear then gets magnified by corporations and bosses viewing employee illness as ‘lost profit’, adding to tensions.

So we have some pretty ridiculous fear cultures operating in the West. In less developed countries, the fear around the body is obviously much less, which probably just reflects a different focus. Survival and God-based fears have a huge hold over 3rd world nations. Apparently a significant portion of Syria’s current problems are based in religious-based fears, and just look at the horrors that has created.

Hi Dave,

Thanks a lot for writing. I must say these Asian students whom you taught at the Uni are lucky to have the opportunity to learn from you.

To talk about the pain, people report less pain in developing nations for various reasons. Here is an example in this recent study which shows low prevalence of chronic pain in developing nations compared to that in developed nations, http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)60805-4/abstract. Talking about situation of pain in Nepal, there are various factors contributing to prevalence of pain. In my experience, pain depends various factors such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, religion, educational status here in Nepal. These have not been tested empirically yet (this is what I am doing in my studies currently). There are some studies on prevalence of pain in Nepal, however, to my knowledge there aren’t any big national level studies to investigate the prevalence of pain nor other contributing factors to pain.

I will share with you one experience. During the community placement with my students in a remote community of Nepal, where we surveyed people living in the community for prevalence of musculoskeletal pain. In first few days of the survey, when over 100 participants were interviewed, none reported any pain. I was amazed to know that, and then I was suspicious. Then, the next day, I went to the survey with my students to learn if that was true. To my surprise, one woman, who was actually holding her lower back and expressing pain via her expressions and moans, said that she had no pain, and she never had any pain in her life time. I then intervened and asked her why she was holding her back? She then said that she had some pain at the lower back, that was actually interfering with her activities of daily living. When I asked her why did she not report that when asked earlier? She said to me, “Who does not have pain? everyone has it. It is that I am not bed bound because of this. However, this has not been allowing me to work normally for a long time now.” On further interview, she reported a pain that was 6/10 in an average in past three months. This intensity of pain in Western world for this long would be very bothersome, I think.

An earlier report by Anderson in early 1980’s demonstrated that prevalence of pain in Nepal is more than the disability caused due to pain. The reason for this is, most people (with low socioeconomic condition) cannot afford to get disabled due to pain. This is because, if they don’t work at their homes or fields or factories, they don’t have money/ food to eat. They have other things to worry about than pain. They think pain is a normal phenomenon that everyone has it. In a way this is a good understanding of pain. Clinicians in developed countries (eg Australia) struggle to hard to educate this to educated people living with pain.

So, meaning of “pain” here and in Australia can be completely different Dave. I find these variations fascinating.

PS. Saurab, I see you’re very interested in how psychology affects health. Me too! I wonder if you’d do me a small favour. Could you ask around to see if the childhood food allergies/anaphylaxis belief has taken hold in the consciousness of Napalese parents? Or is it something particular only to 1st world countries.

Cheers, EG.

Thanks EG physio for the comments. You are right that I am interested in how psychology affects health specifically pain, disability and function.

I will be happy to ask people about food allergies among parents. To my knowledge, parents in Nepal are not much concerned about food allergies, which is probably due to unawareness. Hopefully newer generation parents may be worried about food allergies, but I believe they are very few in number.

I will write back if I have more information on this.

Thanks again,

Regards,

Saurab

This is very interesting. Evidence on pain and pain management from the patients perspective is little known in Nepal. I find this conversation very helpful for my research work. I am literally very thankful for this 🙂 🙂