Words that jump off the page

There’s a thing that happens when you start to get into a bit of philosophy – words that were previously read lightly or taken for granted, can start to jump off the page and ask hard questions. One such word, I’ve noticed, is the seemingly innocuous word, cause.

A basic definition of the word is the relationship between events or things where one is the result of the other. In everyday use we hear it in phrases such as ‘the cause of the accident was inattention due to mobile phone use’, and use of the word is rife in health and medical circles – ‘the cause of death’ or ‘smoking causes lung cancer’.

Spurious correlations

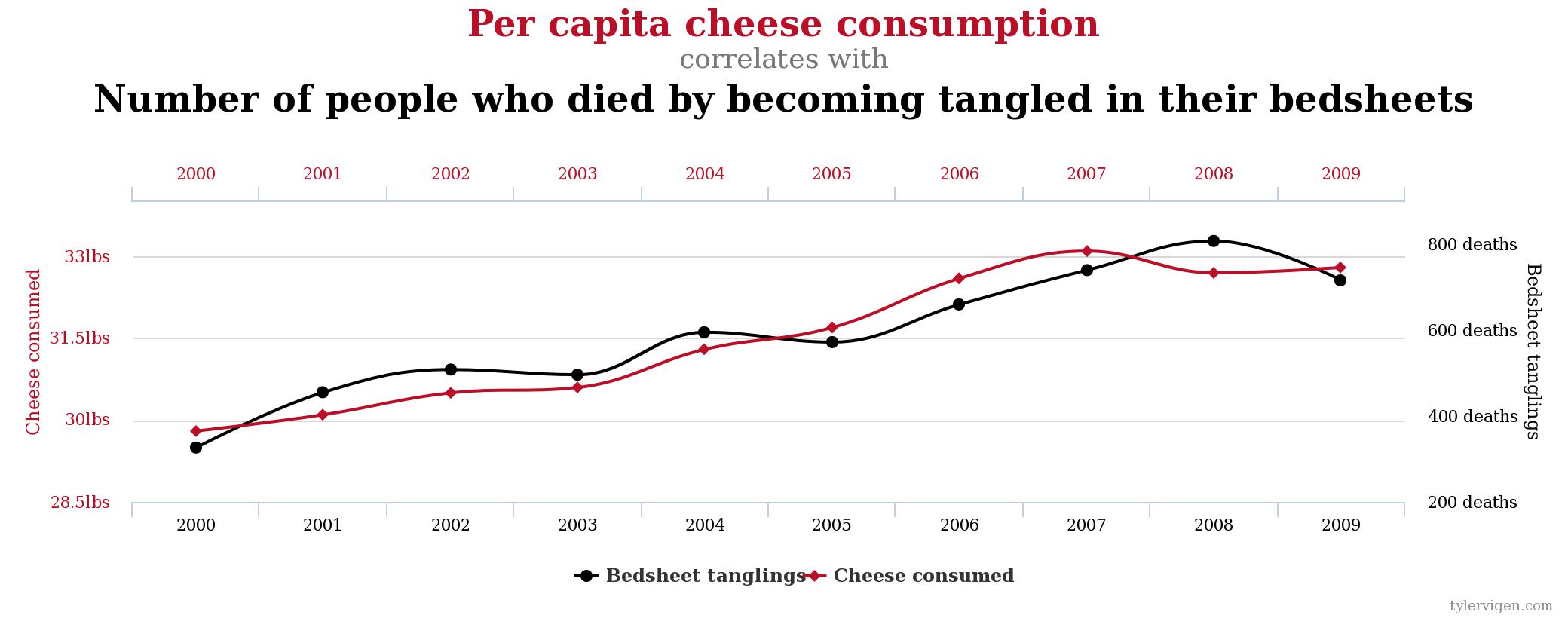

One problem with the word is its frequent conflation with correlation. Two events or things may vary (increase or decrease) together, that is be correlated, but this relationship does not necessarily imply that one is caused by the other. The website Spurious Correlations has some fantastic examples of events that are correlated, but clearly not caused by the other.

The correlation between the number of films that Nicholas Cage appears in during a year, and the number of people who drown by falling into a pool is compelling, but no one would suggest that this graph should be used to deny the planet the silver screen pleasures of National Treasure (1 and 2), Face/Off or the (sadly overlooked for an Oscar) Con Air

However, the following graph does suggest a cover up of a sinister plot involving dairy cows and the bed linen industry

But the whole correlation does not equal causation thing seems to be largely under control, with this statement being common enough in scientific circles, online arguments and blogs to have earned t-shirt slogan status.

A deeper problem, a circular habit

On the other hand, there may a deeper problem with the word cause, one going back quite some time. David Hume* (1711-1776) was a Scottish philosopher who tackled the very idea of cause and effect from a metaphysical (the part of philosophy that deals with basic concepts such as existence, being, knowing, time and space) perspective.

Hume is known as an empiricist philosophically – an argument that suggests that all we know, and can know, comes from what we can experience. In applying this empiricist approach to cause and effect, Hume argued that we could never really experience a cause, but rather could only know that two events occurred closely together in space and time.

Hume suggested that humans tend to jump to explanations about cause through habit or custom. He suggested that because we are accustomed to events in nature uniformly occurring before or after another, or in some regular fashion, that we assume a cause-effect relationship between them. However Hume thought that this situation led to a circular argument that was impossible to escape – our understanding of cause and effect is based on our beliefs about the way nature works, but our beliefs about the way nature works is based on our understanding of cause and effect.

Take, for instance, the example of our experience of weight. We are accustomed -habituated- to experiencing some objects as being heavier than others, and if you ask most people what would happen if you dropped a bowling ball and a feather from the same height at the same time, the likely answer will be that the bowling ball will hit the ground first. If you ask why, inevitably the answer will be because it is heavier – the greater mass of the bowling ball causes the earth to pull on it more (which we experience when we lift it), causing it to fall faster .

But, in one of the most wondrous bits of film you’ll see, it is clear that our experiences in the world can be misleading about cause and effect:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E43-CfukEgs&w=560&h=315]

Ultimately, Hume was skeptical that we could ever truly know that one thing or event caused another

“When we look about us towards external objects, and consider the operation of causes, we are never able, in a single instance, to discover any power or necessary connection; any quality, which binds the effect to the cause, and renders the one an infallible consequence of the other.” (emphasis added)

Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

How Humean are you?

Hume’s works and thoughts have been the source of raging (philosophically speaking) debates based on multiple interpretations of his work. Some people have taken Hume very literally (the very Humean), while others have suggested that Hume never intended to be so skeptical about our ability to have knowledge of causes and effects (the not so Humean). If you really want to dig into this, the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy page David Hume: Causation offers an accessible introduction.

Wherever you stand on the Humean scale, Hume’s idea that we can not experience a cause, and that we should therefore be skeptical about our habitual notions of cause and effect, is at least intended to encourage one to think more carefully about the use of the word, and perhaps examine more closely statements about the relationship between things and events in the world…

Getting to the point… finally

The preceding was a rather long introduction to one of those moments when words jump off the page and ask hard questions. Earlier in the week, a piece appeared on theconversation.com entitled Can the way we move after injury lead to chronic pain? (can you see the sneaky cause-effect insinuation already, hidden in that headline?):

“This important protective strategy [changes in how we move] is mirrored by altered activity in our brains. A large body of evidence shows that short-term pain causes a reduction in activity in the regions of our brains that control movement. (emphasis added)

One doesn’t have to be all that Humean to stop and question the use of the word cause in this example. How could the author know that pain, an intangible, subjective, complex experience, causes some physical change (reduced activity) in the brain?

The large body of evidence cited is a systematic review and meta analysis of neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies investigating “(1) altered activation of S1/M1 during and after pain, (2) the temporal profile of any change in activation and (3) the relationship between S1/M1 activity and the symptoms of pain”. Sounds very correlational, but the cited authors also fall into causal language “We present evidence from a range of methodologies to provide a comprehensive understanding of the effect of pain on S1/M1″ (emphasis added).

Careless thinking

The use of the word cause might be just careless thinking solidified into sloppy writing – a certain metaphysical naiveté, if you will. But it can also be a sneaky way for authors to try to influence you into thinking that they have found a much stronger relationship between things or events, than actually exists – usually at the cost of over-simplifying the underlying complexity of the real relationship. Just a little Humean skepticism might lead to some pointed questions next time you read, or hear, the word cause.

But then again, perhaps it’s all just trivial philosophical semantics?

-Tim Cocks

*My apologies to any Humean scholars, a set to which I clearly do not belong, for the extremely terse and rather simplified presentation of Hume’s ideas.

THE 2017 NOI CALENDAR IS SHAPING UP, HERE ARE THE CONFIRMED DATES

Melbourne, David Butler and Tim Cocks, 31 March – 2 April EP and GMI

Adelaide, Tim Cocks, 26-28 May EP and GMI

Wollongong, Tim Cocks, 14 – 16 July EP and GMI

Darwin, Tim Cocks, 4 – 6 August EP and GMI

Brisbane David Butler and Tim Cocks, 25 – 27 August EP and GMI

Newcastle, Tim Cocks, 8-10 September EP and GMI

Details and dates coming soon for Sydney

Check out our courses page for details and to enquire

DAVID BUTLER IS HEADING TO THE UK AND EUROPE IN 2017

Eemnes, Netherlands – Explain Pain and Graded Motor Imagery April 22-24

York, England – Explain Pain April 26-27

Check out our courses page to make an enquiry

HAVE YOU DOWNLOADED OUR NEW PROTECTOMETER APP YET?

Just search the App Store from your iPad for ‘Protectometer’

Tim, You write well. Does anybody read my blog or writing? I’ve been writing about the word “cause” for years. Does “origin” mean anything to you?

Barrett L. Dorko PT

Hi Barrett

Very kind of you, thank you.

I have read some of your thoughts on ‘origin’ (alas, not all of them), and if an origin (by various definitions) is the point, place or source from which something begins, arises or is derived, then by my way of thinking the origin of the *experience* of pain must be the human.

My best

Tim

Hi Tim,

Really enjoyed this piece, loving the NOI’s incorporation of philosophy to clinical reasoning and education.

I realise you have covered Plato’s cave previously from a patient/client perspective;

https://noijam.com/2016/07/01/the-cave/#more-3691

but consistent with your sceptical/(arguably Socratic) post above, am somewhat compelled to suggest pain scientists/clinicians also are unlikely to ever understand the true nature of Platonic pain?

Max

Hi Max

Indeed! Perhaps the only extent to which we may know the ‘true nature’ of pain is to know one’s own pain? But here we very quickly get into hard problem territory as the corollary question is “what exactly is it to know one’s own experience – that is, to be conscious?” And it’s just a slippery slope (and a wonderful, fantastic, philosophical ride) of isms and ologies from there!

My best

Tim

Perhaps “The Matrix and Me” on my website would be of some interest. Introducing philosophy to manual therapy and context for pain is inevitable. It is thought “elite” in the US and is not all that popular. I call it “curious” and have recently decided that curiosity is genetic. This has numerous implications and I didn’t recognize them for years. I see some people, especially you Tim, as curious. Where that came from is a story. I’ve written about story too.

Barrett L. Dorko PT

Hi Barrett

Thank you – I will definitely check it out.

I’ve had a little push-back (always welcome) when I’ve waxed philosophical – I think sometimes from people who are focussed on content rather than process.

Curiosity may well be genetic, but I do hope that whatever the case, I may be able to encourage a little bit of it in my children. Wouldn’t it be good if it was epidemic – a lot of good could come from a sudden outbreak of thinking!

My best

Tim

Tim,

I have *currently* concluded that curiosity is genetic, but I’m looking for something to explain something about the therapists I’ve come across. Often they’re disinterested in evidence and logic. They are Cypher, but that says nothing about their motivations or “goodness.” I might as well have gotten on them about their height. It has taken me a long time to conclude this, and I know that I might change.

It is the job of the teacher to make something epidemic, which is a function of their charisma, luck, entertainment value and choice of metaphor. Coming along at a certain time seems to help too. NOI seems to have this in spades, which is to say nothing of all the work they’ve put into things. It is enormous.

You’re a voice of reason Tim. Maybe you’ll be honored one day.

Barrett L. Dorko PT

Hi Tim,

I have a strong sense from your writing you really enjoy your philosophy and I very much enjoy reading those posts. My philosophical readings are limited and of a distant past, but I do really look forward to getting some time and mental energy to get stuck into further learning about that aspect of our worlds.

More please,

Max

Hey Max

Thank you for your very kind words. I’ve found philosophy (of mind in particular) a wonderful rabbit hole to lose myself in over the past few years. It has seemed to me for a while now that if what we are interested in is pain (as opposed to nociception – still a very interesting domain, but not the same thing) then we are essentially interested in consciousness, phenomenology and subjective experience. There is such a rich history in these fields that, in my humble opinion, has been completely overlooked by many who study pain. However not everyone agrees!

Whether anybody likes it or note, there will definitely be more of my amateur stumbling through prose philosophical in 2017.

My best

Tim

Hey Tim,

Excellent, I’m with you.

If ‘chronic pain’ and ‘philosophy’ are uniquely human traits, not typically found in other species, would logical deduction (Aristotle) not suggest that they may be related and therefore worthy of further investigation?

This might relate to the issue of placebo/nocebo, for both therapist and client , and what each is likely to utilise, respond to, and when?

I’m sure we used to believe that patients were not capable of understanding neurophysiology, which led to many cases of poor outcomes for clients and empathetic and professional burnout for therapists!

Cheers,

Max